Kaizen: a guide to continuous improvement

Info: 5994 words (24 pages) Study Guides

Published: 10 Nov 2025

Struggling with your Kaizen management assignment? Let our UK-qualified experts guide you to a top grade – send us your brief now for personalised, deadline-driven support. See our management assignment help page for more info.

Kaizen is a Japanese term meaning “continuous improvement,” referring to an approach of constantly making small, incremental changes for the better. Originating in post-World War II Japan, Kaizen emerged as a key principle in the Toyota Production System and later gained global recognition as a foundation of lean manufacturing.

The concept was introduced to the Western world by Masaaki Imai in his 1986 book Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success, which highlighted how a focus on ongoing improvement helped Japanese industries outperform their competitors (Imai, 1986).

At its core, Kaizen is more than a one-time initiative – it is a philosophy and culture that engages all levels of an organisation in continually finding ways to improve processes, reduce waste, and increase quality. Indeed, Kaizen involves everyone from top management to frontline workers in the quest for better methods, embodying the idea that many small changes can yield substantial results over time (Abuzied, 2022).

Over the decades, this approach has proven effective not only in manufacturing but across diverse sectors, from healthcare to software development, as organisations worldwide have adopted Kaizen to drive efficiency and innovation (Brezing, 2023).

Principles of kaizen

Kaizen is guided by a set of core principles that together create a mindset of ongoing improvement. These principles emphasize process, people, and a relentless focus on eliminating inefficiencies. Key tenets of Kaizen include:

Continuous, incremental improvement:

Instead of pursuing radical overhaul, Kaizen favours small, ongoing changes. Problems are seen as opportunities to make things better step by step.

Even modest improvements are valuable, because accumulated minor gains lead to significant long-term advancement (Bhuiyan and Baghel, 2005). Notably, research on quality improvement observes that tiny, continual positive adjustments can yield substantial results over time (Abuzied, 2022).

Focus on eliminating waste:

Kaizen is closely linked to the lean philosophy of removing “muda” (waste) from processes. Any activity that does not add value – such as excess inventory, unnecessary motion, defects, or waiting time – is targeted for reduction or removal.

By streamlining workflows and cutting waste, organisations can deliver greater value to the customer with fewer resources (Bhuiyan and Baghel, 2005).

Employee involvement and empowerment:

A distinctive feature of Kaizen is its reliance on the collective wisdom of all employees. Everyone is encouraged to contribute ideas and identify problems, reflecting the belief that those closest to the work often have valuable insights.

Toyota’s success, for example, has been partly attributed to its Kaizen teian system of employee suggestions, which yields thousands of improvement ideas from workers each year (Liker, 2004). By empowering people at all levels to make changes in their own work areas, Kaizen builds a sense of ownership and accountability for improvement.

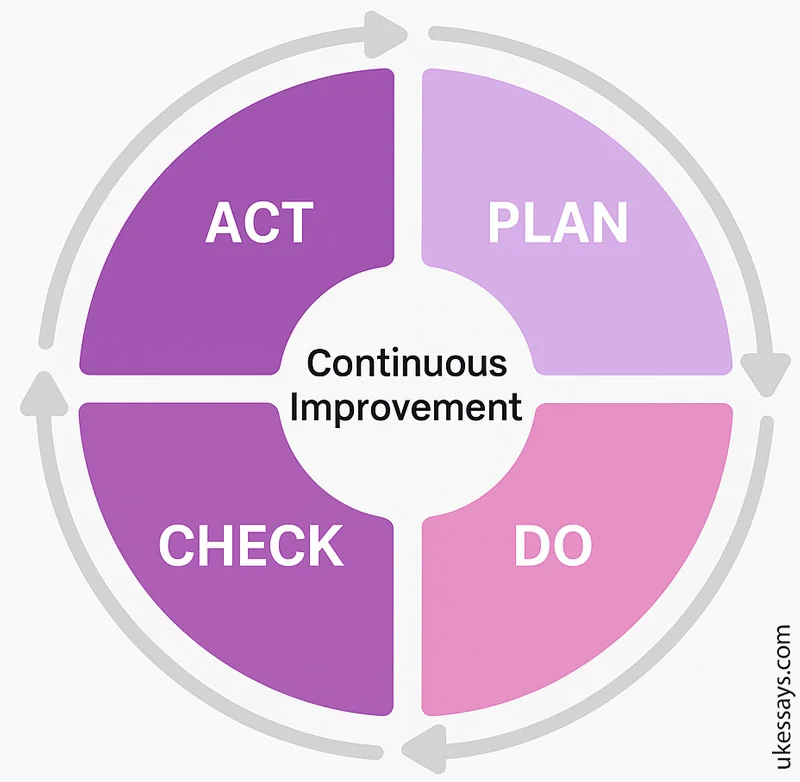

Data-driven problem solving (PDCA cycle):

Kaizen relies on the scientific method to test and implement changes. The Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle – also called Plan-Do-Study-Act – is a fundamental framework in Kaizen initiatives.

Teams plan an improvement (identify a problem and propose a solution), do by implementing a trial change, check the results with data, and act by adopting the change if successful (or iterating again if not).

This structured cycle ensures that improvements are based on evidence and that learning occurs continuously. Using PDCA instils a habit of hypothesis testing and adjustment that drives ongoing learning and refinements (Kaizen Institute, n.d.).

Standardisation and sustainment:

Kaizen operates hand-in-hand with process standardisation. It is often said that “there can be no Kaizen without a standard” – meaning that improving a process requires first establishing consistent best practices as a baseline (Ohno, 1988).

Once improvements are made, they should be documented and standardised so that the new, better method is sustained. This prevents teams from sliding back into old habits and ensures that gains are preserved (Lean Enterprise Institute, n.d.).

In practice, after each improvement, organisations update their standard work instructions or protocols to reflect the enhanced process. This discipline of standardising after improving creates a stable platform for the next round of improvements.

Long-term mindset:

A Kaizen culture takes a long-term view that improvement is an ongoing journey, not a one-time project. Patience and consistency are emphasised. Companies successful with Kaizen often cultivate a “continuous improvement habit” – encouraging staff to always be on the lookout for the next opportunity to make a small positive change.

Rather than seeking perfection in one leap, the goal is to get a little better every day. This mindset, sustained over years, yields remarkable compounding benefits in performance and quality (Imai, 1986). It also fosters adaptability, as organisations become skilled at evolving processes incrementally in response to new challenges.

Underlying all these principles is a philosophy of respect for people and belief in their creative potential. Kaizen-driven organisations develop a supportive environment where making suggestions and questioning the status quo is welcomed.

Problems are not seen as failures of individuals, but as information to improve the system. By embracing front-line ideas, using objective data, and iteratively refining processes, Kaizen creates a culture of continuous learning and innovation.

Kaizen in manufacturing

Manufacturing is the domain where Kaizen practices first took root and where their impact is most famously documented. In factories around the world, Kaizen has been a catalyst for dramatic improvements in productivity, quality, and cost efficiency.

Japanese manufacturers pioneered this approach in the mid-20th century, with Toyota Motor Corporation being the hallmark example of Kaizen’s power. From the 1950s onward, Toyota adopted Kaizen as a core principle of its operations, instilling continuous improvement into every aspect of production (Liker, 2004).

Workers on Toyota’s assembly lines were encouraged to spot issues and suggest fixes on the spot – even small tweaks like rearranging tools or altering a sequence of tasks. Over time, countless such micro-improvements accumulated, enabling Toyota to systematically eliminate waste, streamline assembly processes, and deliver ever-higher vehicle quality. This relentless focus on Kaizen helped Toyota revolutionise the automotive industry, setting new standards for efficiency and reliability (Yoon, 2023).

Other manufacturers soon followed suit, and Kaizen became a cornerstone of lean manufacturing, often synonymous with the Toyota Production System.

In a manufacturing setting, Kaizen takes both formal and informal forms. Daily Kaizen (or “continuous daily improvement”) refers to the habit of workers and teams constantly looking for ways to do their jobs better, even in small ways. For instance, an operator might experiment with a different hand motion to reduce fatigue or re-label a parts bin to prevent mix-ups. These minor changes require no special event – they are part of daily work and are usually implemented by the workers themselves (Imai, 1986). Many factories implement suggestion programs to capture these ideas, rewarding employees for improvements that enhance safety, quality or efficiency.

In addition to the ongoing daily improvements, companies also organise Kaizen events (also known as Kaizen blitz or rapid improvement workshops) in manufacturing operations. A Kaizen event is a focused, short-term project – typically lasting anywhere from a single day up to a week – where a cross-functional team dedicates itself to solving a specific problem or improving a particular process.

For example, a team might hold a 5-day Kaizen event to reorganise a production cell for better flow: on day 1 they map the current process and identify waste, on days 2 – 4 they implement changes (moving equipment, altering layouts, trialling new methods), and on day 5 they measure results and establish new standard procedures.

These events often employ lean tools such as 5S (workplace organisation), value stream mapping, or SMED (rapid changeover) to achieve significant process breakthroughs in a short time.

Kaizen events can generate substantial immediate improvements – for instance, cutting a machine setup time by 50% or reducing defect rates overnight – while also energising employees through hands-on participation (Yoon, 2023).

However, experienced practitioners caution that Kaizen events are not a standalone solution. The gains from an event must be consolidated by proper follow-up and standardisation, or else old habits may reassert themselves and erode the progress made (Haapatalo et al., 2023). Thus, the most effective manufacturers use a combination of regular Kaizen events and a pervasive daily improvement culture.

Management plays a critical role in this system: leaders ensure that time and resources are allocated for improvement activities and that successes are recognised and diffused across the organisation.

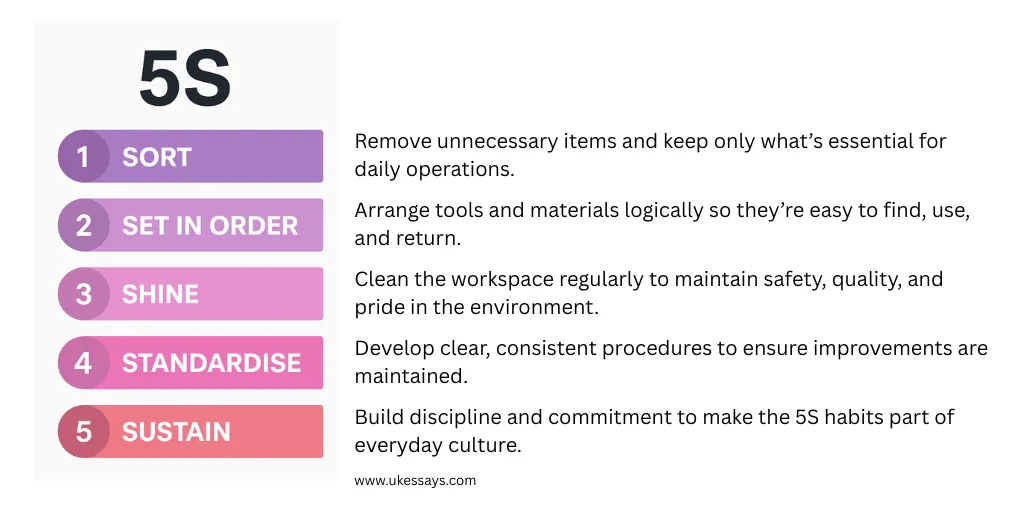

Practically, Kaizen in manufacturing translates into many concrete practices. One example is the widespread adoption of 5S (Sort, Set in order, Shine, Standardise, Sustain) as a way to maintain orderly and efficient workplaces. By continuously improving organisation and cleanliness, companies reduce wasted motion and errors.

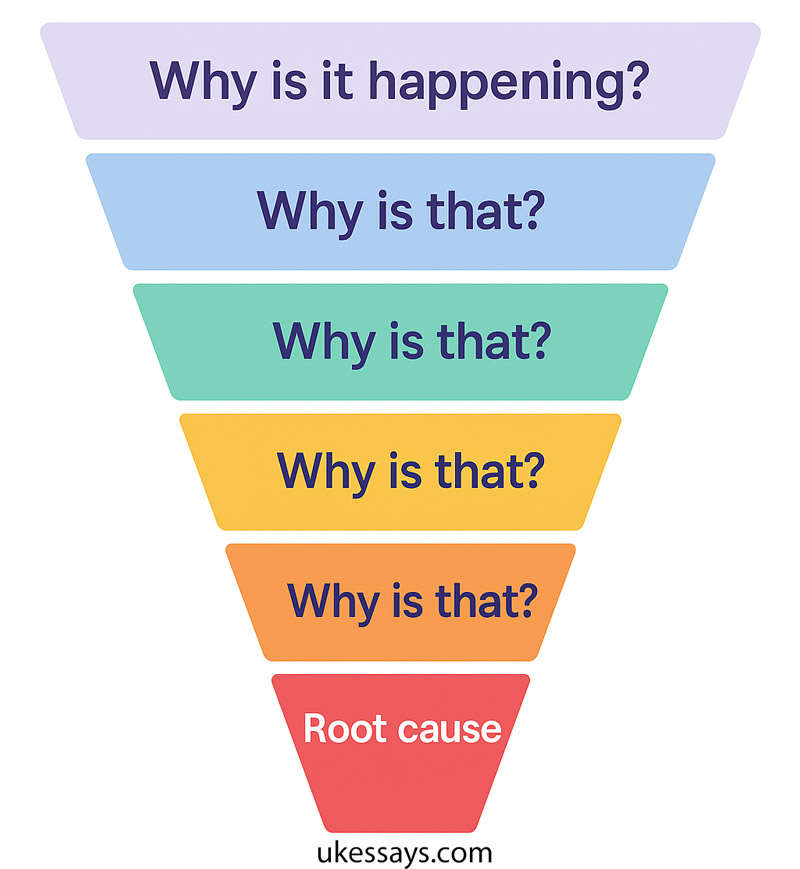

Another example is rigorous root cause analysis (such as the 5 Whys technique) whenever defects or delays occur, with the aim of implementing corrective actions to prevent recurrence.

Above: The 5 Whys root cause analysis is a simple problem-solving method that involves asking “Why?” repeatedly to uncover the underlying cause of an issue. It helps move beyond surface symptoms to identify and address the true root problem.

The process begins with a clearly stated problem. The first “Why?” explores why the issue occurred, and each subsequent “Why?” probes further into the reasons behind the previous answer. By the fifth question (though sometimes more or fewer are needed), the analysis usually reaches the true root cause – the point at which addressing that cause will prevent the problem from recurring.

Developed by Sakichi Toyoda and used extensively within the Toyota Production System, the 5 Whys technique promotes critical thinking, teamwork, and continuous improvement. It’s widely applied across industries, from manufacturing and engineering to healthcare and business management, because it’s straightforward, low-cost, and highly effective when applied systematically.

Over time, these Kaizen-driven efforts yield factories that operate with shorter lead times, lower defect rates, less inventory, and more agile responses to customer demand.

Empirical studies and industry case reports frequently document the benefits: for instance, factories implementing Kaizen have reported double-digit percentage improvements in productivity and significant cost savings through waste elimination (Yoon, 2023).

Just as importantly, frontline workers in Kaizen-oriented plants tend to be more engaged and proactive, since they are empowered to influence their work environment positively. This boost in workforce morale and skill development is an intangible but vital outcome of Kaizen in manufacturing (Bhuiyan and Baghel, 2005).

Applying kaizen across industries

Although Kaizen began in manufacturing, its philosophy of continuous improvement has been applied far beyond the factory floor. In essence, any organisation that has processes – whether in services, knowledge work, or the public sector – can benefit from Kaizen’s systematic approach to identifying and solving problems. Over the past few decades, numerous industries have adopted Kaizen with impressive results, demonstrating the method’s broad versatility (Brezing, 2023).

Healthcare industry

One notable example is healthcare. Hospitals and clinics have increasingly turned to Kaizen (often under the umbrella of “lean healthcare”) to improve patient care processes and reduce errors.

For instance, Virginia Mason Medical Center in the United States famously adapted Toyota’s Kaizen principles into its management system to streamline patient flow and enhance quality of care. By empowering clinical staff to suggest improvements and by running Kaizen projects on issues like surgical scheduling and medication delivery, Virginia Mason achieved significant reductions in patient waiting times, lower infection rates, and higher patient satisfaction (Kenney, 2010).

More broadly, healthcare organisations that embrace Kaizen report benefits such as shorter hospital stays, more efficient use of equipment, and safer, mistake-proofed procedures. Frontline healthcare workers – doctors, nurses, technicians – become active problem-solvers, targeting anything that does not add value for the patient. This has led to innovations like reorganised emergency room triage protocols and simpler medication ordering systems, developed through continuous small changes rather than top-down mandates.

The Kaizen mindset in healthcare also fosters a culture of safety and teamwork, as staff continuously ask “How can we do this better?” and collaborate on solutions.

Service and administration industries

The service and administrative sectors have also seen Kaizen in action. Banks, insurance companies, and government offices use Kaizen to make their largely “invisible” processes more efficient.

For example, administrative Kaizen efforts might focus on reducing paperwork processing time or improving the accuracy of information flows. By mapping out office workflows and eliminating redundancies, organisations have cut response times and improved customer service.

A well-known illustration comes from a major bank that applied Kaizen to its mortgage approval process – by identifying unnecessary approval steps and digitising certain tasks, the bank was able to reduce loan processing time by 30% and improve customer satisfaction.

Retail industry

Similarly, in the retail industry, companies like Tesco have encouraged store employees to suggest improvements in everything from shelf stocking routines to checkout operations. In Tesco’s case, small ideas such as rearranging store layouts to ease bottlenecks and introducing simple visual cues for restocking helped decrease customer wait times and boosted overall sales (Brezing, 2023). These improvements were not expensive interventions, but rather the cumulative effect of many staff-driven suggestions implemented company-wide.

Technology and software industries

In the technology and software sector, Kaizen principles underpin agile and DevOps practices. Software companies have created routines akin to Kaizen by holding regular retrospectives and continuous improvement sprints.

A prominent example is Atlassian’s “Innovation Weeks,” where employees are given time to work on any improvement idea of their choosing (Brezing, 2023). This has led to new product features and internal tools that might not have emerged through formal projects.

The tech industry’s focus on continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) is conceptually aligned with Kaizen – small iterative changes, frequent feedback loops, and learning from failures to improve code and systems.

Even startups employ Kaizen thinking by rapidly iterating their business models and processes in search of better outcomes (often referenced through the Lean Startup methodology, which shares Kaizen’s test-and-learn ethos).

Construction and project management industries

Another arena for Kaizen is construction and project management, where traditional practices have often accepted a certain level of waste (e.g. idle time, rework) as inevitable.

Forward-thinking construction firms, such as Boldt Construction, implemented Kaizen through daily huddles and post-project reviews to capture lessons learned and continuously refine their project workflows (Brezing, 2023).

By treating building projects as processes that can be incrementally improved (rather than one-off endeavors), these companies have reduced on-site inefficiencies and improved safety.

Public sector and education industries

Even the public sector and education have reported success with Kaizen: for example, some city governments applied Kaizen to permitting processes and saw approval times drop significantly, while schools have used Kaizen to improve administrative tasks and classroom workflows.

Across all these examples, the common thread is that Kaizen’s focus on process improvement and people engagement translates well to any environment. The specifics may differ – a hospital’s concerns differ from a factory’s – but the approach (engage employees, map the process, identify waste, implement small fixes, repeat continuously) remains remarkably consistent.

In each case, Kaizen helps break down large, complex challenges (e.g. reducing patient wait time or speeding up software development) into manageable increments tackled one by one. It also helps overcome inertia: rather than waiting for big reforms, organisations see continuous improvement as “the way we do things,” embedding the practice into daily operations.

Moreover, by involving staff in decision-making, Kaizen often improves morale outside of manufacturing just as it does on the factory floor. Employees feel heard and empowered to make positive changes in their work, which can lead to higher job satisfaction and retention.

Implementing kaizen in an organisation

Adopting Kaizen in an organisation involves more than introducing a few new tools – it requires a shift in culture and management approach. Organisations that successfully implement Kaizen typically follow several key steps and practices to ingrain continuous improvement into their operations:

Cultivate a culture of continuous improvement:

Leadership must first establish Kaizen as a core value. This means communicating a clear vision that the company aspires to constantly improve and that every employee’s input is important to that journey.

Leaders should lead by example – visibly engaging in improvement efforts and encouraging openness to change. A culture that supports Kaizen is one where employees are not blamed for problems but instead are urged to voice issues and collaborate on solutions. This often requires training managers to adopt a coaching mindset, guiding teams to solve problems rather than directing them from above (Yoon, 2023).

Importantly, management should allocate time for improvement activities (e.g. dedicating a few hours per week for teams to work on Kaizen ideas) so that employees know continuous improvement is truly a priority and not just a slogan.

Train and empower employees:

Knowledge of basic continuous improvement methods should be spread across the organisation. Many companies start Kaizen implementation by training staff in lean concepts, problem-solving techniques, and data analysis. Workshops on tools like 5S, root cause analysis, or PDCA can build confidence that employees have the skills to contribute.

Beyond formal training, empowerment is critical – employees need the authority to make certain decisions and the resources (or budget) to test small changes. Some organisations create a Kaizen Promotion Office (KPO) or improvement team to support front-line groups in running Kaizen projects. The role of such support teams is to facilitate events, track ideas, and ensure suggestions don’t get lost.

Empowerment also means recognising and rewarding contributions: companies often establish recognition programs for implemented improvements or share success stories company-wide to reinforce that Kaizen efforts are valued.

Implement structured improvement processes (PDCA):

Establishing a consistent method for improvement is a cornerstone of Kaizen. Organisations should encourage teams to use the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle or similar structured problem-solving approach for each improvement opportunity.

For example, if a team identifies a bottleneck in order processing, they would plan a change (Plan), execute it on a trial basis (Do), measure the impact (Check), and if successful, standardise and roll it out (Act). If the results are not positive, the cycle is repeated with a revised plan. By systematically following PDCA, even small improvements are treated as mini-experiments that yield learning.

Many organisations document these cycles in simple forms or software, creating an ongoing log of improvements and their outcomes. This helps in knowledge sharing and prevents the “reinvention of the wheel” in different departments. Additionally, using data to verify results (e.g. did the change actually reduce error rates by X%?) is emphasised to maintain objectivity. Over time, employees become adept at this scientific approach, and it becomes second nature to approach any workplace problem with a hypothesis and test mindset (Kaizen Institute, n.d.).

Conduct Kaizen events for focused improvements:

As part of a Kaizen programme, it is beneficial to identify larger opportunities that may require concentrated effort. Organising periodic Kaizen events (or rapid improvement workshops) can address these opportunities.

For example, management might sponsor a week-long Kaizen event to overhaul the layout of a warehouse section for efficiency, or a three-day event to streamline a billing process involving multiple departments.

In preparing for an event, a specific goal is set (such as “reduce order fulfilment time by 20%”) and a cross-functional team is assembled. During the event, the team steps away from normal duties to map the current process, brainstorm improvements, implement changes on the spot, and verify the results. At the end, they present their results and new standard process to management.

These events generate enthusiasm and fast results, demonstrating the power of Kaizen to the wider organisation. However, it is crucial to follow up after each event: assign owners to each action item and review progress after 30, 60, 90 days to ensure changes are working and lasting (Haapatalo et al., 2023). This follow-through is what turns a burst of improvement into sustained gains.

Standardise and sustain improvements:

A hallmark of effective Kaizen implementation is that improvements are locked in through standardisation. Whenever a better method is developed – whether via a quick suggestion or a major Kaizen event – it should be documented in the relevant standard operating procedures or work instructions. The new process becomes “the way to do the job,” and staff are trained or briefed in the update. This might involve something as simple as updating a checklist or as formal as revising a digital workflow. By standardising, the organisation prevents regression to old habits. It also creates a baseline for the next improvement (Ohno, 1988).

To sustain momentum, many organisations establish routine audits or gemba walks (management go-and-see at the workplace) to verify that new standards are being followed and to spot further improvement possibilities.

Visual management tools, like boards tracking key performance metrics, can be used to make the impact of improvements transparent and keep teams focused on holding the gains. Over time, maintaining a cycle of improvement followed by standardisation builds confidence that Kaizen changes are positive and here to stay.

Measure results and iterate:

Kaizen is an ongoing cycle, so establishing metrics and feedback mechanisms is important to keep driving forward. Organisations should define what success looks like for their improvement efforts – it could be metrics such as defect rates, process cycle time, customer satisfaction scores, cost per unit, safety incident counts, or other performance indicators relevant to their context. When Kaizen changes are made, these metrics are monitored to quantify the impact.

Celebrating achievements (for example, announcing that “Production line A increased output by 15% after recent Kaizen improvements”) reinforces the value of the work. If an initiative did not achieve the expected result, that too is treated as learning rather than failure, prompting analysis and further action.

Regular review meetings (often weekly or monthly) are held by department heads or continuous improvement teams to review recent Kaizen ideas implemented and to remove obstacles if any are stalled. Through such governance, Kaizen becomes a managed process with accountability.

Furthermore, knowledge sharing sessions can be instituted where teams present their improvement projects and outcomes to peers. This cross-pollinates ideas and maintains enthusiasm. Ultimately, the goal is to create a self-sustaining flywheel of improvement: measure performance, implement ideas, see results, motivate the team, then look for the next round of improvements.

By following these steps, organisations create an environment where Kaizen can flourish. It’s important to note that the leadership commitment cannot be overstated – management must not only permit Kaizen, but actively drive it by providing clear direction, resources, and recognition.

There may be challenges along the way, such as resistance to change or the temptation to revert to old habits, especially under pressure. Overcoming these challenges requires persistence and sometimes cultural change management techniques (for example, showing quick wins to sceptics, or integrating Kaizen goals into performance evaluations).

Some organisations find it useful to start Kaizen implementation in a pilot area or model line, then expand as success is demonstrated. Others may bring in experienced consultants or partner with institutes to build capability. Whatever the approach, the transformation into a Kaizen-oriented organisation is an investment in long-term excellence. When done properly, the payoff is significant – a workforce that continuously improves every process, resulting in superior performance, higher quality, lower costs, and an agile enterprise capable of adapting readily to new challenges.

Benefits of kaizen

Organisations that embrace Kaizen can expect to see a wide range of benefits, both tangible and intangible. Some of the well-documented advantages include:

Improved quality and fewer defects:

Because Kaizen relentlessly targets the root causes of problems and emphasises doing things right, it leads to more consistent processes and higher-quality outputs. Incremental fixes – like error-proofing a step or upgrading a tool – reduce variation and mistakes.

Over time, products and services have fewer defects, rework is minimised, and customer satisfaction rises. Many firms credit Kaizen for helping them achieve world-class quality standards (Liker, 2004).

Higher efficiency and productivity:

Eliminating wasteful steps and optimising workflows means that work gets done faster and with less effort. Kaizen often results in shorter cycle times for processes, whether it’s assembling a product or processing a customer request. Even modest time savings, when added up across many steps and repetitions, allow teams to accomplish more in the same amount of time.

In manufacturing, this can translate to higher production output per worker or per machine. In services, it may mean handling more customer transactions per day. Efficiency gains through Kaizen also free up capacity, allowing organisations to grow without proportional increases in resources.

Cost reduction:

Many Kaizen improvements have a direct financial impact by cutting costs. Streamlined processes use fewer resources – for example, less material waste, lower inventory holding costs due to just-in-time principles, or reduced overtime thanks to better work balance. Additionally, improved quality lowers the cost of poor quality (scrap, warranty claims, etc.).

Unlike large capital projects, Kaizen achieves savings through better use of existing assets and people, often with minimal expenditure (Bhuiyan and Baghel, 2005). This makes it a very high return-on-investment approach to improvement. Organisations practicing Kaizen often find that cumulative small savings substantially improve the bottom line over time.

Employee engagement and development:

A perhaps less immediately obvious benefit of Kaizen is the positive effect on workforce morale and skills. When employees are asked to participate in improvement and their ideas are implemented, they feel valued and heard. This involvement can increase job satisfaction and create a sense of pride and ownership in the workplace. Workers become more engaged, as their roles are not just to perform tasks but also to think about how to make those tasks better.

Kaizen also provides continuous learning opportunities; staff learn problem-solving techniques, data analysis, teamwork and leadership skills by participating in Kaizen activities. This investment in human capital can pay off in a more capable, adaptable workforce. Companies often note that attrition falls and internal promotion pipelines improve when a Kaizen culture is nurtured, because employees are growing and finding fulfillment in improvement work (Yoon, 2023).

Greater agility and innovation:

Continuous improvement makes an organisation more flexible and responsive to change. Because Kaizen encourages trying out ideas on a small scale, organisations become more experimental and willing to innovate. Instead of being stuck with rigid procedures, the culture accepts change as normal. This agility means that when market conditions or customer requirements shift, Kaizen-oriented companies can adapt their processes faster.

Additionally, the habit of ongoing improvement can lead to innovative breakthroughs. While Kaizen is usually about incremental changes, the accumulation of many small ideas can occasionally coalesce into significant innovations in how work is done or even in the products and services offered. In essence, Kaizen keeps the organisation in a constant state of evolution and prevents complacency.

Sustainable competitive advantage:

Because Kaizen improvements are continuous, the benefits tend to be compounding and sustainable. In contrast to one-off initiatives that might give a short-term boost, Kaizen embeds improvement into the company’s DNA. This creates a moving target for competitors.

For example, if two companies start at the same performance level but one practices Kaizen and the other does not, a year later the Kaizen company will likely have better quality, lower costs, and faster delivery due to hundreds of incremental gains made in that year.

Over multiple years, that performance gap can widen significantly. Competitors who try to imitate a few practices might find it hard to catch up because what they are copying is a continuous improvement system rather than a static model. In this way, Kaizen can form a core of an organisation’s long-term competitive strategy (Kaizen Institute, n.d.).

It is important to note that the magnitude of these benefits depends on the level of commitment to Kaizen. Companies that truly integrate Kaizen in their operations often report transformative results – such as double-digit productivity improvements annually, dramatic quality turnarounds, or turnarounds from chronic losses to profitability.

Even companies that are already high-performing can use Kaizen to maintain their edge and keep finding new efficiencies. The benefits span financial outcomes, customer outcomes, and people outcomes, aligning well with balanced scorecard perspectives (financial, customer, internal process, learning and growth).

That said, Kaizen is not a quick fix but a discipline; the benefits accrue through persistent, ongoing effort. Organisations must therefore view these gains as the payoff for sustaining the Kaizen journey.

Challenges and critical success factors

While Kaizen offers many benefits, implementing it is not without challenges. Organisations can encounter obstacles that hinder their continuous improvement efforts if not proactively addressed. Common challenges include:

Cultural resistance:

Kaizen represents a change in mindset, and some employees or managers may resist it, especially if they are used to traditional top-down decision making or are uncomfortable with change. Initially, workers might be skeptical about sharing ideas if they fear criticism or have seen past suggestions ignored. Managers might also feel threatened by giving more autonomy to front-line staff.

Overcoming this requires change management – communicating the purpose of Kaizen, creating a safe environment for voice, and gradually building trust by acting on ideas and avoiding blame for failures. Leadership must consistently reinforce that Kaizen is a positive, expected part of everyone’s role.

Lack of immediate results:

Kaizen’s incremental nature means big results take time. In impatient corporate environments that demand quick returns, sustaining support for Kaizen can be hard if there isn’t an early visible win. Stakeholders may ask “Is this worth it?” if they do not understand the compounding effect. It’s crucial to set realistic expectations and highlight qualitative improvements (like improved teamwork or small fixes) early on.

Many firms start with a pilot project that can deliver a quick win to demonstrate Kaizen’s potential. Showcasing a successful Kaizen event or a cluster of implemented ideas in the first few months can help build momentum and justify continued efforts.

Difficulty in sustaining improvements:

One of the most cited pitfalls is the tendency for improvements to fade away over time. This can happen if standardisation and follow-up are weak – people might slowly revert to old habits, especially if there is turnover or if management attention shifts. Studies have noted that maintaining long-term results after Kaizen events can be challenging (Haapatalo et al., 2023).

To counteract this, organisations need to institutionalise the changes. For example, making new procedures part of training for new employees, having regular audits on key processes, or assigning process owners responsible for monitoring compliance.

It’s also beneficial to periodically revisit past Kaizen improvements to see if further refinement or support is needed. If an improvement isn’t holding, treat that as a new problem to solve (rather than a failure) – perhaps the solution wasn’t robust enough or new issues emerged. In essence, sustaining Kaizen requires vigilance and sometimes additional rounds of PDCA on the solutions themselves.

Measurement and crediting issues:

Sometimes improvements are hard to measure or aren’t immediately visible in high-level metrics, causing them to be undervalued. Additionally, in large organisations it might be unclear who gets credit or how to attribute gains when many small changes collectively impact performance. This can lead to less motivation if not handled well.

The solution is to measure what you can (even if it’s local metrics for a process) and to broadly recognise teams for contributions. Even anecdotal evidence of improvement or a before-and-after observation can be powerful to document. Over time, building a repository of success stories – “this team’s idea saved 100 labour hours per month” or “Kaizen effort in department X reduced customer complaints by 20%” – can justify the approach to all stakeholders.

Integration with daily work:

Employees often struggle to find time for Kaizen on top of their regular duties. If the workload is high and schedules are tight, continuous improvement can slip down the priority list. This is why management must integrate Kaizen into daily routines.

Some companies implement brief daily or weekly team huddles to discuss problems and ideas, ensuring that continuous improvement has a dedicated slot. Others free up staff periodically by backfilling positions or rotating responsibilities to allow participation in improvement workshops.

A common saying in lean is “we can’t afford not to take time to improve” – emphasising that firefighting all day without improving guarantees more fires tomorrow. Scheduling and incentives should align so that employees are not penalised (implicitly or explicitly) for stepping away to work on improvements.

Overemphasis on tools over mindset:

There is a risk that companies get very enthusiastic about lean tools (like 5S, Kanban boards, Six Sigma techniques) and deploy them mechanically without fostering the underlying culture. Kaizen is not just a checklist of techniques; it’s a way of thinking. If the workforce goes through the motions (cleaning the workspace, holding formal meetings) but doesn’t truly internalise continuous improvement, results will be limited.

It’s important to continually reinforce the principles and not just the practices. For instance, implementing 5S should be framed not as just tidying up, but as enabling easier identification of issues and respect for the workplace. Training should connect each tool to the bigger picture of Kaizen philosophy. When people understand the “why,” they are more likely to use tools effectively rather than treat them as box-ticking exercises.

Addressing these challenges requires strong leadership and a strategic approach. Critical success factors for Kaizen implementation include executive commitment, robust communication, and persistence.

Leadership must allocate necessary resources (time, budget for improvement where needed, training) and also be patient – cultivating Kaizen can take months or years to fully bear fruit. It is also valuable to celebrate successes publicly to reinforce positive behavior and to create internal advocates.

Many companies find that once a few teams achieve notable improvements and enjoy the process, they become champions who mentor others. In addition, leveraging expertise – whether through hiring experienced continuous improvement professionals or learning from other organisations’ experiences – can jump-start progress and help avoid common pitfalls.

Finally, adaptability is key: organisations should be willing to adapt the Kaizen approach to their unique context. For example, a software company might implement Kaizen through weekly retrospectives and hackathons, whereas a hospital might use daily safety briefings and monthly improvement projects. The fundamental principles remain, but the mechanics can be tailored.

Kaizen itself is about learning and adapting, so it is fitting that implementing Kaizen is a learning process too. Companies should be ready to refine their approach, perhaps treating the implementation plan as yet another PDCA loop – planning the rollout, doing it, checking what works or not, and adjusting accordingly. By doing so, they exemplify continuous improvement in the very act of introducing continuous improvement.

Ready to take the stress out of your Kaizen management assignment? Get expert help from our UK-qualified writers today – share your brief and get tailored support designed to meet your goals and deadlines. See our management assignment help page for more info.

Example student-written essays on Kaizen:

- Literature Review On The Kaizen Theory Management Essay (Undergraduate 2:1)

- Continuous Improvement as a Business Strategy (Undergraduate 2:1)

References and further reading:

- Abuzied, Y. (2022) ‘A practical guide to the Kaizen approach as a quality improvement tool’, Global Journal on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 5(3), pp. 79–81.

- Bhuiyan, N. and Baghel, A. (2005) ‘An overview of continuous improvement: from the past to the present’, Management Decision, 43(5), pp. 761–771.

- Brezing, C. (2023) ‘Kaizen examples: continuous improvement across industries’, LCMD Blog. Available at: https://www.lcmd.io/en/blog/kaizen-examples-continuous-improvement-across-industries (Accessed 10 Nov 2025).

- Haapatalo, E., Reponen, E. and Torkki, P. (2023) ‘Sustainability of performance improvements after 26 Kaizen events in a large academic hospital system: a mixed methods study’, BMJ Open, 13(8), e071743.

- Imai, M. (1986) Kaizen: The key to Japan’s competitive success. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kaizen Institute (n.d.) ‘What is Kaizen – Meaning of Kaizen’. Available at: https://www.kaizen.com/what-is-kaizen/ (Accessed 9 Nov 2025).

- Kenney, C. (2010) Transforming health care: Virginia Mason Medical Center’s pursuit of the perfect patient experience. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Lean Enterprise Institute (n.d.) ‘Kaizen’ (Lexicon). Available at: https://www.lean.org/lexicon-terms/kaizen/ (Accessed 9 Nov 2025).

- Liker, J.K. (2004) The Toyota Way: 14 management principles from the world’s greatest manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Ohno, T. (1988) Toyota production system: Beyond large-scale production. New York: Productivity Press.

- Yoon, D. (2023) ‘A guide to sustained improvement with the Kaizen methodology’, KaiNexus Blog, 21 February. Available at: https://blog.kainexus.com/improvement-disciplines/kaizen/a-quick-guide-to-the-kaizen-methodology (Accessed 8 Nov 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: